NEW YORK (AP) — New York City’s police commissioner, who has found himself caught at times between loyalty to his officers and demands from the public and politicians for greater police accountability, announced Monday that he is retiring.

James O’Neill said he will leave for a private sector job in December, a little more than three years after he took charge of the nation’s largest police department. Chief of Detectives Dermot Shea will succeed him, Mayor Bill de Blasio said.

O’Neill led the police department’s move away from controversial “broken windows” policies, guided its response to pipe bomb blasts and a deadly truck attack, and has overseen continuing drops in crime. He called leading the NYPD the “best job in the world.”

But over the last few months, the career policeman has been increasingly under fire amid a tug-of-war between reform advocates and police unions over discipline, transparency and the level of support he’s shown for officers walking the beat.

The strongest rebuke came in August, when the city’s largest police union held a rare no-confidence vote and called for O’Neill’s resignation after he fired an officer over the 2014 chokehold death of Eric Garner.

The union, the Police Benevolent Association, said the firing left the NYPD “rudderless and frozen” and signaled to officers that the boss didn’t have their back.

O’Neill said Monday that the decision to fire Officer Daniel Pantaleo, five years after Garner’s dying words “I can’t breathe” became a rallying cry against alleged police brutality, weighed heavily on him, but did not factor into his retirement.

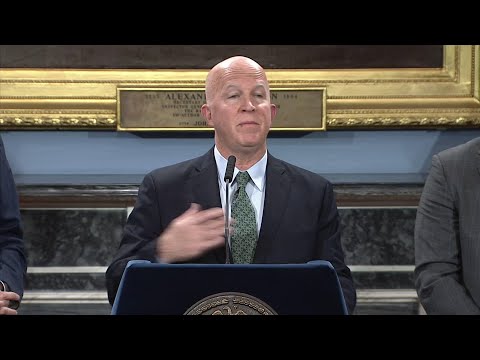

“This is the right time for me,” O’Neill said at a news conference on the leadership change.

“This job comes with a lot. It comes with a lot of pressure. This (job) is all I have thought about for the last 38 months — 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. It’s all you think about, is keeping the people of this city safe, and it was an honor to serve.”

Shea, raised in Queens by Irish immigrants, started with the NYPD in 1991 as a patrolman in the Bronx. He rose to prominence at police headquarters as the department’s statistical guru and last year overhauled the division that handled the sexual misconduct investigation of Harvey Weinstein.

De Blasio said Shea is “one of the best-prepared incoming police commissioners this city has ever seen” and knows the department and the city “inside and out.”

Patrick Lynch, the president of the Police Benevolent Association, said he wants to work with Shea to “combat the current anti-police atmosphere and make positive changes that will improve the lives of our police officers and every New Yorker we protect.”

Civil rights activist Rev. Al Sharpton called Monday for an immediate meeting with Shea to discuss how policing policies affect people of color.

Donna Lieberman, the executive director of the New York Civil Liberties Union, said the department under Shea “must prioritize transparency, accountability, and repairing relationships with the people they serve.”

Tina Luongo, of the Legal Aid Society, said in a statement that de Blasio should have embraced transparency and solicited input from city residents before picking a new police commissioner.

In Shea’s tenure as chief of detectives, the police department has expanded its database of alleged gang members — often black and Hispanic men and women — and codified expansive DNA collection practices, Luongo said. Her organization provides legal services for people who cannot afford lawyers.

“This will be more of the same, and our clients — New Yorkers from communities of color — will continue to suffer more of the same from a police department that prioritizes arrests and summonses above all else,” Luongo said.

O’Neill joined the NYPD as a transit officer in 1983 and spent more than three decades with the department before de Blasio appointed him in September 2016 as commissioner.

He got a sense of the job’s frenetic pace on the first day, when a pipe bomb exploded in Manhattan’s bustling Chelsea neighborhood, injuring 29 people.

O’Neill was quick to move the department from a focus on the broken windows theory, which viewed low-level offenses as a gateway to bigger crimes, to a neighborhood policing model designed to give officers more time to walk around and interact with people in the communities they police.

But critics contend that broken windows policing hasn’t really gone away, and that officers are finding new low-level targets — such as immigrant delivery people who get around on electric bikes — and that trust between officers and many residents remains low.

In June, O’Neill made headlines by apologizing for the violent police raid at the Stonewall Inn in 1969. Speaking on the 50th anniversary of the LGBTQ uprising that followed, O’Neill called the police department’s actions “discriminatory and oppressive.”

This year, O’Neill grieved as two police officers were killed in separate friendly fire incidents, and he declared a mental health emergency amid a rash of officer suicides.

___

Follow Sisak at twitter.com/mikesisak